Streamlining Ohio’s Energy Legislation: Key Reforms for Efficiency and Competition

Ohio’s energy laws are a maze of overlapping rules that stifle innovation & raise costs. eGeneration breaks down the key issues in the Ohio Revised Code and proposes bold reforms to: Simplify renewable mandates Boost real competition Unleash "resilient" microgrids Unify state energy efforts

NEWS

Jon Morrow

8/24/202510 min read

By Jon Paul Morrow M.Econ., M. Poli.Sci.

Ohio’s energy laws span multiple code sections that often overlap and complicate policy. By consolidating and clarifying these statutes, Ohio lawmakers can promote freedom, encourage real competition (that benefits consumers), and align with strategies advocated by the energy policy experts at the eGeneration Foundation. Below, we identify top issues in the Ohio Revised Code (ORC) related to energy, explain the current verbiage, propose streamlined language, and justify each reform.

Issue 1: Consolidating Renewable Energy Mandates into Technology-Neutral Goals

Present Law: Ohio’s Renewable Portfolio Standard (RPS) is codified in ORC 4928.64. It currently mandates that by 2026, 8.5% of electricity sold by utilities must come from “qualifying renewable energy resources,” with detailed yearly benchmarks and carve-outs . For example, the law specifies “that portion shall equal eight and one-half per cent of the total kilowatt hours… by the end of 2026”. These resources are defined to include solar, wind, biomass, hydro, etc., with additional criteria and compliance payments for shortfalls. Separate provisions in ORC 3706.40 created special categories like “qualifying solar resource” limited to certain in-state solar farms, illustrating how current statutes narrowly promote specific technologies.

Proposed Language: Replace the rigid RPS mandates with a technology-neutral clean energy standard focused on reliability and emission outcomes. For instance, repeal ORC 4928.64’s percentage requirements and enact language such as: “Each electric utility shall ensure a diverse, reliable power supply and pursue cost-effective emissions reductions, without mandated quotas for specific energy sources. All low- or zero-emission generation technologies (e.g. advanced nuclear, efficient natural gas, hydro, etc.) shall be eligible equally to meet any state clean energy goals.” This consolidated standard would treat all energy forms on equal footing – ending special carve-outs for intermittent sources (which is the government picking winners and losers) – and encourage the “best of the above” solutions rather than forcing “all of the above”.

Justification: The current RPS language is lengthy and prescriptive, effectively favoring wind and solar. However, evidence shows that heavily subsidized intermittent sources “make our grid more fragile, more expensive, and more dependent on foreign supply chains”. Ohio has been “paying for two grids – one intermittent, one reliable – and getting none of the promised emissions reductions” under these mandates. Streamlining the law to be technology-neutral provides freedom for utilities to choose the most reliable and economical clean energy. It also fosters competition among energy technologies based on performance rather than on mandates or subsidies. Importantly, this reform does not ban wind or solar, but it removes their special status. As the eGeneration Foundation argues, Ohio needs a “Best of the Above” policy focusing on solutions that actually improve the grid and economy – not feel-good quotas. By allowing advanced nuclear, efficient gas, and other innovative sources to count toward broad clean energy goals, Ohio can still pursue environmental objectives more effectively. This change aligns with strategies to reward genuine carbon reductions (for example, nuclear “carbon reversal” credits in lieu of traditional renewables credits) and would position Ohio competitively against other states on energy cost and reliability, benefitting consumers in the long run.

Issue 2: Reforming Competitive Retail Markets to Protect Consumers and Reliability

Present Law: Ohio restructured its electric industry in 1999 (SB 3), declaring generation and supply a “competitive service” rather than a state regulated utility service. ORC 4928.03 provides that since January 1, 2001, “retail electric generation… services supplied to consumers… are competitive retail electric services that the consumers may obtain… from any supplier”. In practice, this means utilities no longer own most generation; instead, power is bought via regional markets (PJM Interconnection) and consumers can pick Competitive Retail Electric Service (CRES) providers. The law’s intent was to lower prices through competition, but in reality it created an unecessarily complex and costly marketplace. Multiple ORC sections (4928.01, 4928.08, etc.) set up rules for certification of competitive suppliers, standard service offers, and so on. This patchwork has not guaranteed lower costs or reliability – even Ohio’s industrial base faces “soaring bills” and blackout risks under the current regime.

Proposed Language: Amend Ohio law to restore state oversight of resource adequacy and consumer pricing. This could involve revising ORC 4928.02 and 4928.03 to redefine the state’s electricity policy: for example, “ensure reasonably priced and reliable power for all Ohioans, whether through market contracts or regulated arrangements, as the public interest requires.” The statute should explicitly empower Ohio to implement a hybrid model if needed (which, it is, if the state of Ohio does not reregulate to truly competitive arrangements) – allowing competitive generation where it clearly benefits consumers, but authorizing state intervention (e.g. utility-built generation or long-term contracts) to secure affordable baseload power. One approach is adding a provision that “if competitive markets fail to provide sufficient generation at stable, low cost, the Public Utilities Commission may approve utility-owned generation projects or contracts to protect consumers.” Additionally, strengthen consumer protection in retail choice by requiring that any marketer’s offer provides a tangible benefit (such as a lower rate or value-added service) compared to the default utility service. Unnecessary sections can be consolidated or repealed – for example, simplifying the certification and monitoring of CRES providers in ORC 4928.08 into a single, clear rule that all suppliers must transparently beat the standard offer price or else refrain from misleading solicitations.

Justification: The goal is to “err on the side of freedom” for Ohio to chart its own energy destiny and ensure real benefits for its citizens, rather than being handcuffed to a dysfunctional market. Today, Ohio’s hands-off approach has left it at the mercy of PJM’s regional auctions and out-of-state bureaucrats. As one analysis put it, Ohio’s “deregulated façade” has CRES companies competing “not to lower your bill – but to see who can fleece Ohioans more creatively”. Meanwhile, critical baseload plants struggle to stay open, and grid reliability is at risk. By streamlining the code to allow a proactive state role, Ohio can ensure real competition – i.e., competition with other states to offer the most stable, low-cost power to attract jobs. This might mean Ohio refocuses on what worked in the past: “cheap, reliable baseload energy – coal, nuclear, and natural gas plants that ran 24/7” under accountable oversight. Aligning with eGeneration’s strategy, lawmakers could declare a limited energy emergency authority to fast-track new reliable generation (for example, advanced molten salt reactors or combined-cycle gas plants). In sum, the law should prioritize consumer benefit and grid security over dogmatic adherence to a market structure. Simplifying or reversing parts of Ohio’s deregulation code would give the state flexibility to prevent blackouts and price spikes – ultimately delivering the competition that matters (state-versus-state economic competitiveness grounded in affordable energy) rather than “competition for its own sake” that leaves Ohioans paying more.

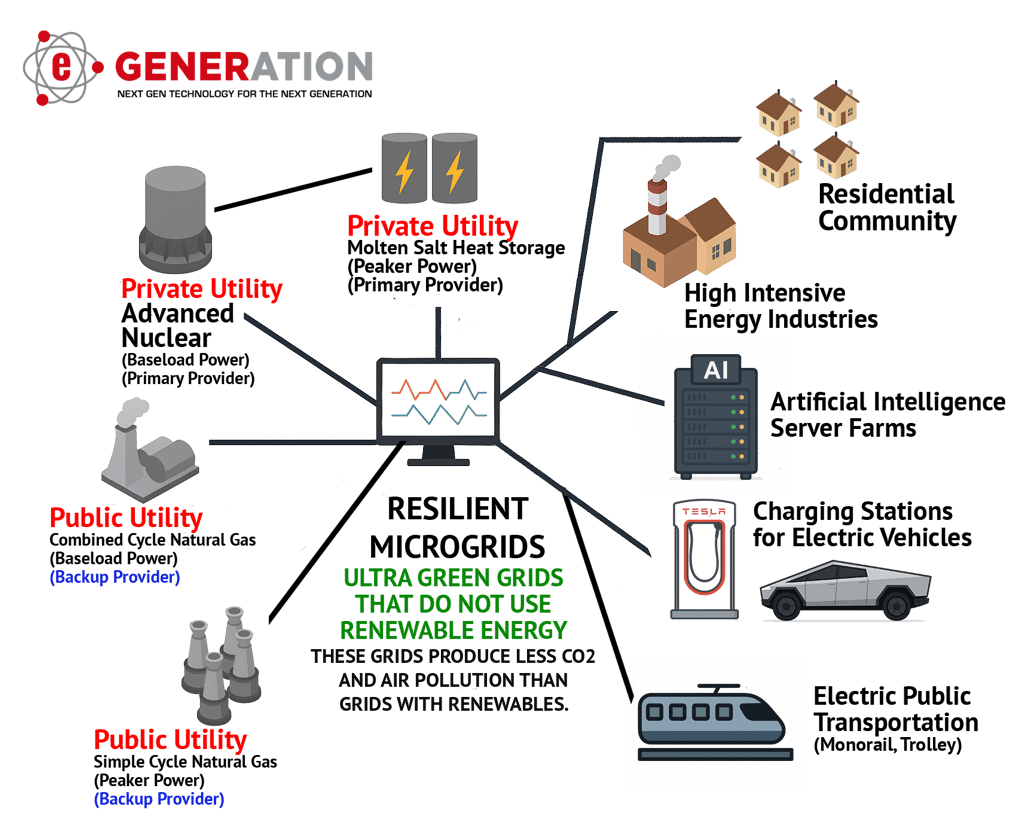

Issue 3: Streamlining Regulations for Microgrids and Behind-the-Meter Generation

Present Law: Historically, Ohio law strictly limited behind-the-meter (BTM) generation. A company could only self-generate power on its own premises to avoid being deemed a public utility. Recent legislation (e.g., H.B. 15 of 2023) relaxed this, allowing BTM projects that serve multiple co-located mercantile customers, even if the generator is owned by a third party, so long as it’s on property controlled by either the customer or generator. S.B. 52 (2021) also added new ORC sections (4906.21–4906.212) requiring detailed decommissioning plans for wind and solar farms, reflecting growing regulation of renewable project siting. The current BTM framework imposes a geographic limit – e.g. S.B. 2 proposed a rule that the generator must be within one mile of the consumers to qualify as a local microgrid – and initially considered barring utilities from owning new BTM microgrids (except those already in pilot programs). In short, Ohio’s codes on distributed generation are nascent and somewhat piecemeal: they permit new microgrid arrangements but with constraints (distance limits, ownership restrictions) spread across different sections.

Proposed Language: Unify Ohio’s approach to distributed energy by creating a single “Microgrid and Distributed Generation” chapter in the ORC (or a new subchapter of 4928). This statute would explicitly allow: (a) any behind-the-meter or private microgrid serving one or multiple customers (including an entire campus or industrial park), so long as participants consent and the system meets safety standards; (b) participation by electric distribution utilities (EDUs) and electric utilities (EUs) in such projects, with Public Utilities Commission oversight to prevent cost-shifting to non-participants. We recommend expanding the geographic limit – e.g. replace the “within one mile” rule with a more flexible standard (perhaps up to 50 miles within Ohio for truly local networks) to facilitate more opportunities. Proposed language could state: “Contiguous or nearby properties (within [50] miles) may interconnect private generation and loads as a microgrid, without being considered a public utility, provided the microgrid operates primarily to serve its members and does not unfairly impact non-member customers.” The law should also clarify that utilities may partner in or operate microgrids (removing any blanket prohibition) if doing so enhances reliability and customers bear the costs voluntarily. Finally, consolidate any project requirements – e.g. a general decommissioning obligation for all large generation installations – into this chapter, instead of separate rules just for wind/solar. This ensures consistent standards without singling out specific technologies unnecessarily.

Justification: These changes reduce regulatory complexity and uncertainty that currently impede innovative energy solutions. By having a clear, broad authorization in one place, Ohio can unleash private investment in advanced small reactors, solar-plus-storage microgrids, waste-to-energy units, and more – all on the condition that they improve resiliency and operate without subsidies from unwilling ratepayers. The justification is evident in Ohio’s recent momentum: H.B. 15 and S.B. 2 opened the door for on-site generation sharing, recognizing that companies want reliable power independent of congested grids created by PJM. Expanding the radius and allowing utility participation will only accelerate this trend. Analysts note that enabling “unrestricted BTM deals” will “unlock private investment and partnerships” for projects like small modular reactors on industrial brownfield sites. Properly regulated, such microgrids boost overall grid robustness – they can island during outages and even support the wider grid with extra power or ancillary services. Crucially, the proposed law protects non-participants: current rules already “explicitly prohibit an EDU from charging non-participating customers for any costs” of BTM generation, and that principle remains. Thus, we maximize freedom for communities and industries to secure their own energy (some may even choose to “opt for forming their own microgrid” to escape high regional market prices) while maintaining fairness. Aligning with eGeneration’s strategy, Ohio should leverage microgrids and “Turning Point” reactors as a selling point to attract high-tech industry. Streamlined BTM legislation will make Ohio a national leader in next-generation energy deployment, all without burdening taxpayers or other ratepayers – a win-win for economic development and consumer resilience.

Issue 4: Unifying State Energy Development Authorities and Incentives

Present Law: Ohio’s efforts to promote energy development are scattered across different chapters and programs. For example, the Ohio Air Quality Development Authority (OAQDA) (ORC Chapter 3706) can finance projects via bonds for “air quality” purposes - which has led to a very jaded liberal renewable energy bias. In 2019, HB 6 temporarily used OAQDA to administer nuclear and solar credit subsidies (ORC 3706.40–3706.65), an unusual repurposing now largely repealed. Separately, Ohio recently created the Ohio Nuclear Development Authority (ONDA) (ORC Chapter 4164) within the Department of Development, tasked with advancing nuclear technology. ONDA has specific powers in law, but there are proposals to expand its role (e.g. to chase federal nuclear waste funds). Additionally, Ohio’s renewable energy credit system (4928.645) and other incentives operate independently. The result is a patchwork: multiple definitions of what counts as “renewable” or “advanced energy” (with one list in 4928.01(A)(37) and another concept of “qualifying resources” in 3706.40), multiple funds and authorities, and a lack of one coherent strategy.

Proposed Language: Merge and streamline these provisions by creating a single framework for state-supported energy innovation. One approach is to legislate an “Ohio Energy Freedom Act” consolidating the mandates of OAQDA and ONDA into a coordinated structure. For instance, amend ORC 4164 to absorb relevant sections of 3706 – giving ONDA authority not just over nuclear, but over any high-value energy project that enhances Ohio’s grid or environment (including advanced nuclear, energy storage, waste-to-fuel conversion, etc.). The law could establish an Ohio Energy Development Consortium (building on proposals for an Ohio Nuclear Development Consortium) to execute projects via public-private partnership. In practical terms, this means repealing narrow statutes like the leftover “qualifying solar resource” credit program, and instead authorizing a general Energy Infrastructure Fund. That fund could be capitalized by innovative means (for example, transferring unused state accounts or leveraging private investment matches, as suggested by eGeneration’s ONDC plan). Proposed language might read: “The Ohio [Energy] Development Authority is empowered to coordinate all state energy investments and credit programs. It may issue credits or shares to utilities and investors who fund approved in-state projects that improve grid reliability, reduce waste or emissions, and lower consumer costs. All existing energy credit obligations (renewable, nuclear, or otherwise) are hereby unified under this program.” By doing so, the Revised Code sections for RPS compliance, nuclear development, and air quality bonds can be shortened and harmonized, pointing to one comprehensive program.

Justification: This reform recognizes that Ohio’s best strategy is to focus on outcomes (reliable, affordable, cleaner energy) rather than carve-outs for particular industries. Consolidating authorities removes duplication and bureaucratic silos – as one proposal notes, making a single entity the “sole representative” for pursuing federal funds or major projects can “reduce duplication of efforts across agencies” and ensure a unified strategy. It also provides clarity to businesses: rather than navigating separate programs for renewables vs. nuclear vs. pollution control, investors would have one front door for state support. This change is in line with the eGeneration Foundation’s strategy to leverage “dormant capital” (like unclaimed funds) and “catalyze private-sector investment in high-value infrastructure without increasing taxes”. For example, using a portion of the state’s unclaimed funds or a small fee on waste disposal to fund energy innovation has been suggested – a unified authority could implement such creative financing swiftly. Moreover, by broadening the definition of eligible projects, Ohio can encourage competition among all energy forms to solve problems. A consolidated credit system could reward a nuclear plant that “consumes nuclear waste and produces medical isotopes” just as easily as it could a carbon-capture facility or a waste-to-energy plant. The justification is that consumers benefit when the state’s limited support is targeted at real solutions that lower long-term costs or clean up legacy waste, rather than being spread via mandates or one-off bailouts. In summary, unifying these laws would make Ohio more nimble in attracting next-generation energy projects – be it a **fast-spectrum reactor factory or a hydrogen hub – and ensure that regulations and incentives are succinct, strategic, and oriented toward freedom through innovation rather than favoritism.

By addressing these key areas – from simplifying renewable energy rules, to reforming the electric market structure, to unleashing microgrids and unifying state efforts – Ohio can rewrite its energy laws in a more succinct, effective way. The proposed language changes favor maximum freedom for enterprise, genuine competition that benefits consumers, and alignment with forward-looking strategies (such as those championed by eGeneration). The result will be legislation that is clearer and more adaptable to the real-world energy challenges of the 21st century, positioning Ohio as a competitive leader rather than a follower in energy policy.